Research shows that even in the most primitive societies, music and religion are intertwined. The transition of humanity and the entire universe from the realm of nothingness to existence began with the Creator’s command, “Kün!” (Be!), that is, with a sound. Later, the special call to humanity, “Elestü bi’rabbiküm” (Am I not your Lord?), represents the Almighty Creator’s acknowledgement of human beings as His interlocutors.

On the other hand, the end of all created things will, so to speak, occur with the sound of an instrument — the blowing of the Sûr (Trumpet) by Isrāfīl (a.s.). Between these two sounds, human beings, the most precious beings in the universe, perhaps due to the divine breath within them — “[When I have fashioned him and breathed into him of My Spirit, fall down before him in prostration.]” (Al-Hijr 29) — have always been drawn to beautiful sound. For these reasons, it is inconceivable that religion would be deprived of beautiful sound. The remarkable development of mosque and tekké music in our tradition is evidence of this. Numerous studies on the effects of sound on both spirit and matter also demonstrate its invisible but profound influence. Of course, since this writing is more of a personal essay than a scientific article, we will not delve deeply into these scientific studies.

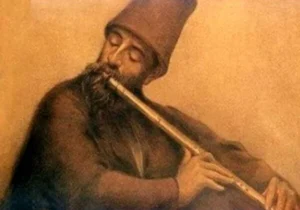

As is well known in musical circles, tekkes (Sufi lodges) have long served as centers of music for the public, with especially the Mevlevi tekkes functioning as conservatories, a tradition that continued for centuries. Undoubtedly, the value and significance that Mevlânâ Celâleddin-i Rûmi (Rumi) attributed to music — particularly to the ney and rebab among Turkish classical instruments — has been highly influential in this regard. The fact that in the very first line of the first twelve couplets he personally penned in the Masnavi-ye Sharif, he mentions the ney, clearly shows the importance he placed on this instrument. Let us share that couplet here:

Ez cüdâyihâ hikâyet mî-küned

(Listen to the ney, how it tells a story,

How it laments the pains of separation.

As is well known, the ney represents the human being in Mevlevi tradition. The cutting of the reed from the cane symbolizes the human’s birth and the cutting of the umbilical cord. The human body has nine outward openings, and similarly, the ney has nine holes: six in the front, one in the back, and two—one at the head and one at the tip. After being fashioned from the reed and having its mouthpiece made, the ney begins to emit laments expressing the sorrow of leaving its homeland. This perfectly symbolizes humanity’s tearful departure from its true home, paradise, to the alien world of earth. As it is played, the ney’s burning sound grows more intense day by day. Similarly, as a person burns with the fire of love and the sorrow of separation, beautiful sounds and words begin to emerge. The teachings of Mevlâna, who was consumed by the fire of love, reaching every corner of the world, are a prime example of the beauty of this sound.

When closely examined, it would not be an exaggeration to say that the concept of the ney completely encompasses the Mevlevi order. At the beginning of our article, we touched upon the relationship between religion and music; examining this specifically in the context of the meanings embedded within the Mevlevi āyin (ritual ceremonies) is essential for understanding the subject. Of course, this is a topic that would require a lengthy academic treatment. Here, we will strive to express it briefly.

Mevlevi Āyin (Ritual Ceremony)

A Mevlevi āyin consists of four main sections called selams. Before the selams, the ceremony begins sequentially with the Na’t-ı Mevlâna (a poem praising Mevlâna), the kudüm drum performance, a ney taksim (improvisation), and the peşrev (instrumental prelude). After the fourth selam, there is the final peşrev, the last yürük semai (a rhythmic instrumental form), a final improvisation performed with an instrument other than the ney, and the aşr-ı şerif (the concluding part). Discussing the symbolism of the part up to the first selam will clarify the meaning attributed to the ney. The Almighty Creator first created the light (nur) of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him). For this reason, the āyin-i şerif begins with the Na’t, which speaks of the Prophet, praises Him, and contains prayers and blessings upon Him.

Next, the kudüm drumbeat expresses the command of “Be!” (Arabic: Kun!), uttered by Allah the Exalted. Following this, the ney taksim performed represents the divine breath mentioned in verse 29 of Surah Al-Hijr, as referenced earlier in our text. The ney symbolizes the human being, and the breath of the neyzen (ney player) is the Divine Breath. The extended ney improvisation tells of the earthly life filled with laments and suffering. When the taksim ends, the peşrev begins. At the conclusion of the peşrev, a very short ney taksim is performed, symbolizing the blowing of the Sûr (Trumpet) by Isrāfīl (a.s.). Then, the entrance to the first selam takes place, during which the semah dancers, who until that moment have been revolving wearing black cloaks symbolizing the earth, remove their cloaks upon the blowing of the Sûr. Revealing the pure white skirts underneath—which represent shrouds—they symbolically step into the gathering place of the Resurrection.

As can be seen, the ney is not merely a musical instrument but also conceals a profound and intense philosophy within the chambers of its nodes. To those who close one eye, look inside the ney, and ask, "It's empty inside. How can it produce sound?" you can have them read this text and then ask, " Are you sure it's truly empty inside? ".

Muhammed TÜRE

Bartın University

Faculty of Theology

Lecturer of Islamic Arts and Religious Music,